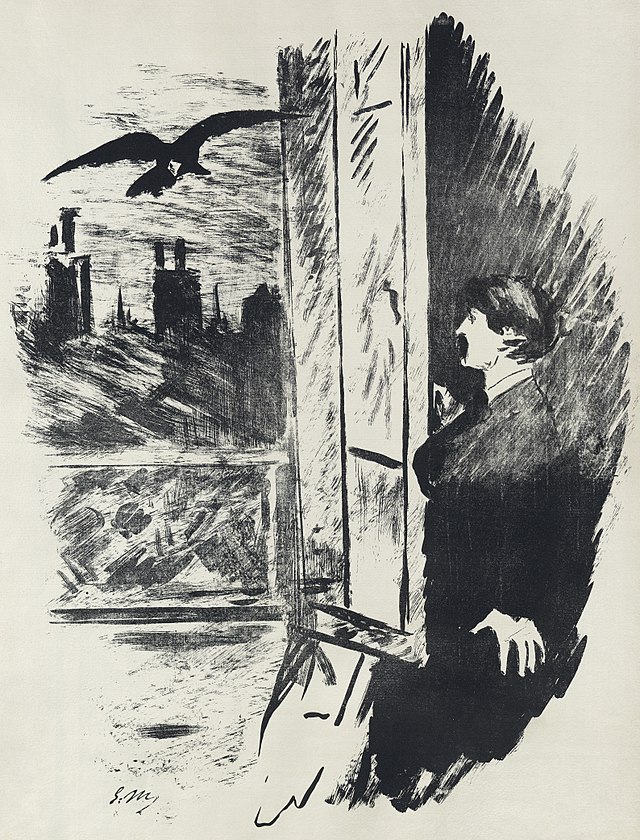

Author: Anonymous

Letters Written on the Death of Ilyitch Lain

Told through the medium of a series of letters, A lecturer of metaphysics employed by a renown seminary in St. Petersburg has decided to end his life in three days in an act of pseudo-theomachist martyrdom. He begins to have second thoughts after witnessing a man smoking through the window. 4200 words.

The Misadventures of Killbo Stabbins: Hafling Serial Killer Series III: The Accursed Alliance

Killbo wasted no time making his way to the clown’s lair and promptly explained that the deed was done. “Now it’s time for you to meet you end of the contract,” he said. “What contract?” The clown looked puzzled. “Don’t toy with me, beast.” “I’m being sincere,” the clown said, blinking absently and looking dumbfounded. … [DO NOT CLICK]

The Misadventures of Killbo Stabbins: Halfling Serial Killer Series II: Fate of the Half-Pint Exorcist

Killbo dusted his clothes off and took a moment to collect himself. The clown’s trash portal had transported him close to the cathedral. There it was, a gray blight on the horizon, dreary in its somber majesty. It seemed to cast a shadow over the entire city. Killbo never like churches. Churches were for people … [DO NOT CLICK]

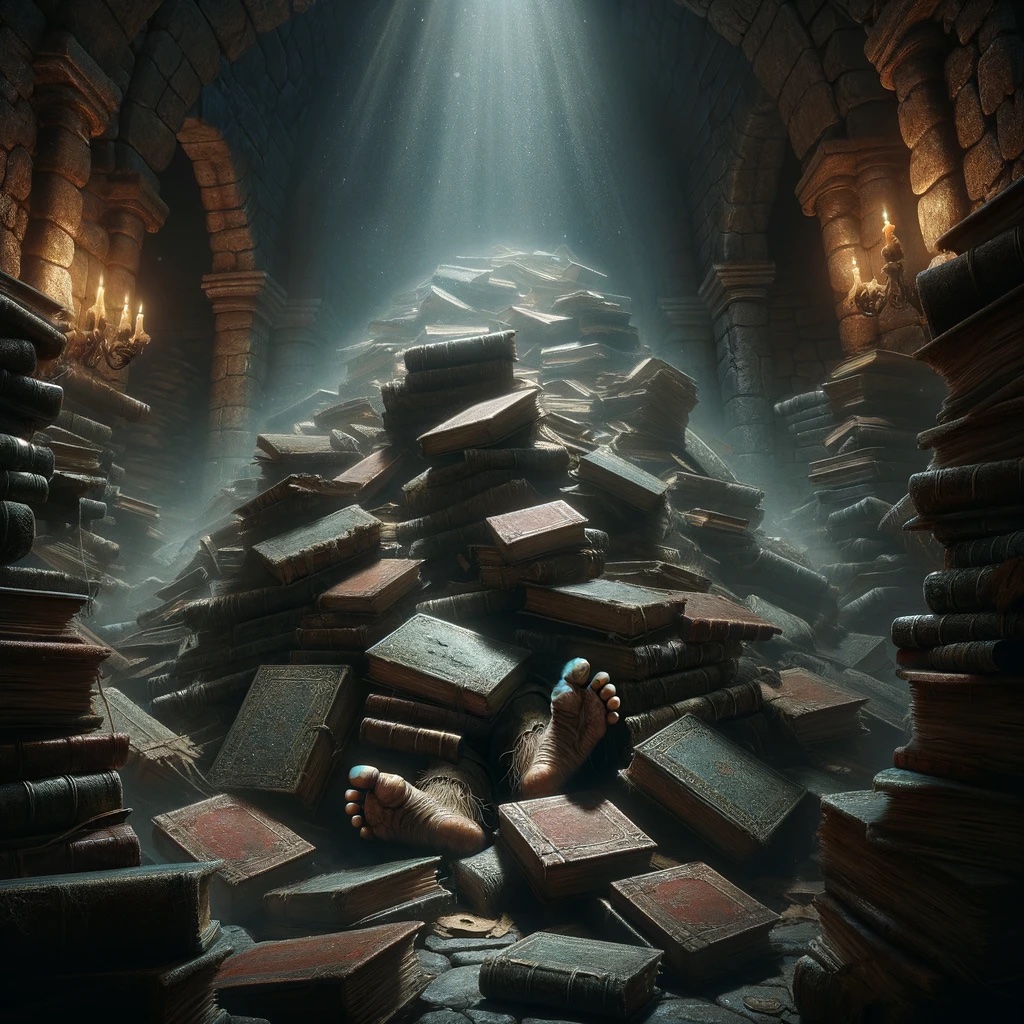

The Misadventures of Killbo Stabbins : Halfling Serial Killer Series I: Contract of the Clownomancer

Tiny hairy feet stalked the night, the footsteps of a miniature beast on the prowl. The dirty alleys of Hobbitville stank of refuse, the spoiled trimmings of pork haunches, half eaten fruits, nibbled fish bones, moldy cheese rinds. Such were the many-faceted remnants of the sundries purloined from the tables of the rich by the … [DO NOT CLICK]